Patterns of Arabia

The different cultures of Arabia are rich with history, philosophy, and the arts. The arts of a culture, like architecture, decoration, interior design, and handicrafts, are distinguished by the patterns of the land and its people. In this article, we highlight 4 patterns found across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and its sisterly Arab states.

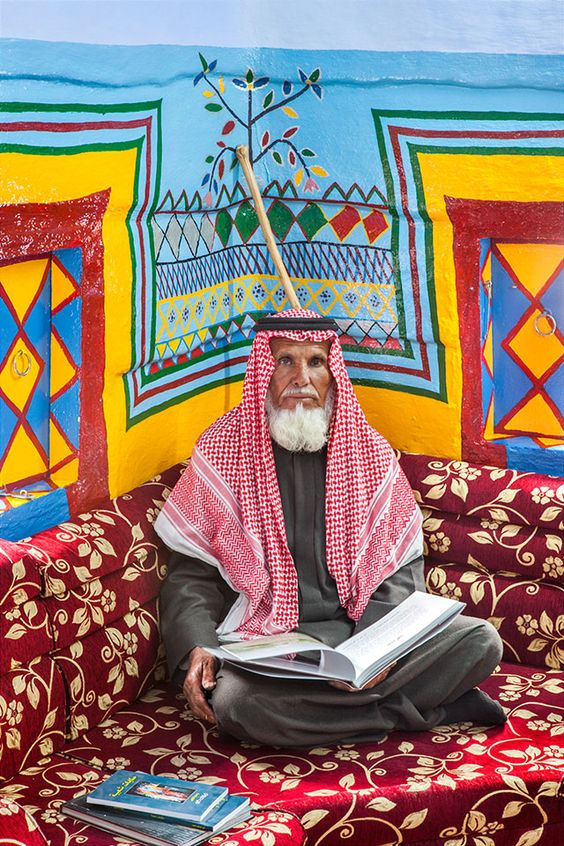

Al-Qatt Al-Asiri

Al-Qatt Alasiri is a female interior wall decoration pattern in Southern Saudi Arabia, chiefly the Asir province. Asir is an isolated, rugged region and is home to the tallest mountains in the Kingdom. The patterns of Taqteet can be found across all of Asir, from the villages on its plains to the region’s hanging villages (Hanging villages – villages accessible to inhabitants by ropes and ladders). The practice of Taqteet enhances social bonding within the community, and highlights the important role of women in Asir.

The pattern consists of geometric symbols; squares, triangles, branch-like figures, and parallel lines. Symbols reflect the people, religion, and surrounding environment. For example, triangles represent women and children. Regularly occurring colors in the practice are red, mustard yellow, and green, which are made vibrant with sharp black lines. The technique of combining shapes and colors is said to be spontaneous and unplanned.

Up until 80 years ago, the materials and tools were sourced from natural materials. The base is formed from white gypsum. Dyes and painting tools were created from local plants, trees, and herb. Ground coal and tree gum made black dye, crushed Al-Meshuggah stones and tree bark carmine made red/orange dye, blue nile sedimentary rock made blue dye, and herbs made green dye. Paint Brushes for detailed work are made from chewed twigs of myrrh or siwak trees, feathers, and wool. Paint brushes for larger areas are made from cloth.

Historically, the main purpose of Al-Qatt Al-Asiri was to adorn the house’s internal walls, especially the Majlis room (Majlis – room designated for receiving guests). It was traditionally a female practice, with the transmission of the knowledge passing through generations of women. Now, it is practiced by both female and male architects, interior designers, and fashion designers and its purpose has expanded to adorn more textiles like clothing, accessories, and furniture.

A prominent figure in the practice and preservation of Al-Qatt Al-asiri is Fatima bint Ali Abu Qahas, whose art is now displayed in the Rijaa Al-Maa Museum.

Al-Sadu

Al-sadu is a Bedouin weaving technique that produces tightly woven, durable fabric from natural fibers found in the surrounding environment. The Bedouin are nomadic Arab tribes who have inhabited the desert regions of the Arabian Peninsula, Mesopotamia, the Levant, and North Africa. Hence, no one country is solely home to Al-sadu, and the pattern is found across two continents and multiple countries.

The Sadu pattern reflects the desert environment in its most simple and pure form. This is acheived by utilizing geometric shapes, rhythmic repetition, symmetry, and figurative symbols. Common motifs are stars, meteorological phenomena, sand dunes, desert planes, and tribal animals, especially camels, for their important role in transportation, food, and textile production. Regularly appearing colors are black, brown, beige, and red for a pop of color.

The process begins with the Bedouin men shearing the tribes’ sheep, camels, and goats. Then, the fibers are cleaned and dyed by the Bedouin women using local plant extract dyes such as henna, saffron, cactus, turmeric, and indigo. Afterwards, the wool is spun on a drop spindle to create yarn. Finally, the yarn is woven on a floor loom using a warp-faced plain weave. The bearers of the practice were predominantly older women, who transmitted the practice to the younger female generations. Al-Sadu highlights the important role of Bedouin women in the tribe.

Historically, Al-Sadu was a major source of income for Bedouin women for its variety of uses. The Sadu fabric was purposed in many industries; carpets, tents, camels, travel gear, tools like resilient garments, and decorative items for camels and horses. In the modern day, the Sadu is less functional and more of an aesthetic expression of deep tradition and a cultural decorative. The pattern is featured on everyday items such as wallets, rugs, and decorative pillows.

Nowadays, master weavers are older women whose numbers are dwindling due to the decline of the nomadic tribal tradition in favor of modern urban lifestyles. To preserve the practice, Kuwait established Sadu House in 1980 to showcase Kuwaiti Bedouin Sadu. In addition, by 2020, KSA , Kuwait, and UAE Sadu are all documented in the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage. Qatar displays Qatari Bedouin Sadu in the National Museum of Qatar’s 2023 project “The Majlis: A Meeting Place” and in the 2022 World Cup.

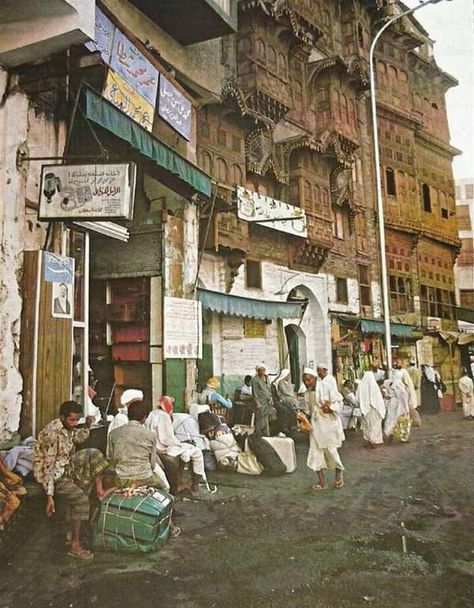

Al-Rawashin

Rawashin are traditional projected lattice windows/balconies with intricate wood works from the Hejaz region. The Hejaz lies in the Western province of the Kingdom, and is the cradle of the two Holy Mosques. Thus, it has seen the rise of different Muslim cultures and civilizations throughout the centuries. The blend of these cultures emerged as one, and the architectural representation of that is the Rawashin.

The Rawashin industry was established during the Abbasid Era, but truly flourished during the Ottoman Era. Initially, the Rawashin windows were imported from India, the East African Coast, and Malay, but it eventually became a local industry.

The pattern, engraved in the wood parts, consists of geometric, floral, and topographic motifs.The geometric shapes include star pentagons, hexagons, and octagonal shapes. The floral symbols are usually inspired by nature, and include iris, carnation, and lady’s mantle. In addition, calligraphic phrases from the Quran or Duaa are written in Al-Thuluth font on the Rawashin. The amount of decoration, size, carvings, and embellishments of the Rawashin indicate the economic and social status of the homeowner.

In addition to its aesthetic aspects, the Rawashin have many functions. Besides covering external openings, they allow control of indoor air ventilation, indoor lighting, and indoor temperatures. The openings of the Rawashin allow for sunlight to enter without an increase in internal temperatures because of the wood’s insulation property. The small engravings also allow for the air to flow inside the house, and in times of extreme heat,the air passes through the water-filled jugs inside the Rawashin to act as natural air conditioning. In addition, the small engravings preserve privacy for the inhabitants while simultaneously allowing them to see outside.

The industry of crafting Rawashin has declined due to the influence of modern life that swept through Jeddah, Makkah, Madinah, and the rest of the Kingdom. There remain Rawashin in the dilapidated coral houses in the old town of Jeddah, which is now being revived and preserved to be fitting of its World Heritage Site label. While the old houses of Makkah that adorned Rawashin were demolished during the Holy Mosque expansion, the Rawashin beautify many modern hotels surrounding the Holy Mosque in Makkah and in Madina. A few Rawashin houses remain in Taif, and surprisingly, in the abandoned Tabuk of Al-Wajh.

Sami Angawi, a prominent architect heavily invested in preserving, restoring, and reviving traditional Hejazi architecture, designed and built the infamous Hejazi Angawi House. The Hejazi Angawi House displays the essence of Hejazi architecture and beauty of the Rawasin.

Najdi Doors

Najdi doors are unique in their decoration and embellishments. The embellished Najdi doors usually lead to the Majlis as a treat for guests coming in or passing by. Even the door separating the Majlis from the rest of the house is lavishly decorated in Najd. Najd Province lies in the central Region of the Kingdom, and encompasses the Capitol Riyadh as well as Diriyah, Riyadh, Unaizah, Buraida, Sudair – with each area having a distinct door decoration pattern.

The pattern consists of intersections of lines, inner rings, and triangles. The symbols included reflect the region’s nature; common motifs are wild plants, flowers, palm fronds, the sun and sun rays, and mountains, which are often depicted as triangles carved into the door. In addition, the front of the door displays the name of the family, date, and some expression of praising God and prayers to the Prophet.

The door’s level of embellishment is a typical indicator of the house owner’s wealth and social status. Another indication of wealth is when there are two doors providing access to the home; guest door and family door. In that case, the family door is typically narrow and less ornamented, while the guest door is wide, decorative and colorful. However, there is an exception to the rule when the house owner is wealthy but avoids high levels of ornamentation due to their personal religious convictions.

Najdi doors have functional aspects as well. The meaning of the door depends on two factors: 1) how the inhabitants themselves use the door and 2) whom the door serves (men/guest door or private family door).First, the inhabitants use the description of the door as a form of directions/guide to the house for guests, such that the guest is able to identify the correct house (the house whose door fits the description).Second, in the case of two entrances to the house, the difference in levels of decoration between the doors guides the guests to the door designated for them, such that the guest will approach the more lavish door (the guest door). Thus, the traditional doors of Najd function as a non-verbal communication tool between the house owners and guests. Finally, the front doors of traditional Najdi homes were never directly facing each other for the sake of privacy.

The construction of Najdi doors, although a declining tradition, is still passed down from one generation of men to the next. In fact, most of the crafters are sons and grandsons of carpenters.

Leave a comment